|

William James On Genius & Insanity

Introduction

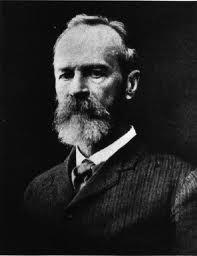

Below, one of the best comments on intellect, psychopathic tendencies and genius I have heard, from one of *my* heroes, William James.

His comments absolutely tally with my own observations and experiences over the years.

It is simply *not enough* just to be very smart in order to be a genius.

Genius is *thinking PLUS doing*.

The kind of *sheer effort* that comes with creating new things, bucking the pressure of society, teachers, everyone; taking the abuse and negative feedback and all the failures along the way; making something (an idea, a piece of music, a question etc) the centre of your life for weeks on end and to the exclusion of all else *demands compulsion and obsession* to bring something into being against all the odds or else what you have is a few notebooks full of clever scribbles that are thrown away when the executor of your will auctions off your house.

Silvia Hartmann

Author, The Genius Symbols

"Vires Per Virtutem"

William James On Genius & Psychopathy

Similarly, the nature of genius has been illuminated by the attempts, of which I already made mention, to class it with psychopathical phenomena.

Borderland insanity, crankiness, insane temperament, loss of mental balance, psychopathic degeneration (to use a few of the many synonyms by which it has been called), has certain peculiarities and liabilities which, when combined with a superior quality of intellect in an individual, make it more probable that he will make his mark and affect his age, than if his temperament were less neurotic.

There is of course no special affinity between lack of mental balance as such and superior intellect, for most psychopaths have feeble intellects, and superior intellects more commonly have normal nervous systems. But the psychopathic temperament, whatever be the intellect with which it finds itself paired, often brings with it ardor and excitability of character.

The unbalanced person has extraordinary emotional susceptibility. He is liable to fixed ideas and obsessions. His conceptions tend to pass immediately into belief and action; and when he gets a new idea, he has no rest till he proclaims it, or in some way "works it off." "What shall I think of it?" a common person says to himself about a vexed question; but in an "unbalanced" mind "What must I do about it?" is the form the question tends to take.

In the autobiography of Mrs. Annie Besant*, I read the following passage:

"Plenty of people wish well to any good cause, but very few care to exert themselves to help it, and still fewer will risk anything in its support. 'Someone ought to do it, but why should I?' is the ever reechoed phrase of weak-kneed amiability. 'Someone ought to do it, so why not I?' is the cry of some earnest servant of man, eagerly forward springing to face some perilous duty. Between these two sentences lie whole centuries of moral evolution."

True enough! and between these two sentences lie also the different destinies of the ordinary sluggard and the psychopathic man.

Thus, when a superior talent such as intellect and a psychopathic temperament coalesce in the same individual, we have the best possible condition for the kind of effective genius that gets into the biographical dictionaries.

Such men do not remain mere critics and understanders with their intellect.

Their ideas possess them, they inflict them, for better or worse, upon their companions or their age.

*Annie Besant was Krishnamurti's discoverer/teacher.

Suggested Reading: The Genius Symbols

|

"Deepest, heartfelt thanks to Silvia Hartmann and the powers that be for presenting Project Sanctuary and the whole paradigm that radiates around it - or perhaps from it. First time I have ever been able to honestly say “life-altering transformational!" Laura Moberg

"Deepest, heartfelt thanks to Silvia Hartmann and the powers that be for presenting Project Sanctuary and the whole paradigm that radiates around it - or perhaps from it. First time I have ever been able to honestly say “life-altering transformational!" Laura Moberg